Summary

The Truss government wants to achieve “growth, growth and growth”, more specifically: “a trend rate of growth of 2.5%”. But with a tight labour market that has already contributed significantly to the middling growth achieved in the 2010’s, the government is betting big on inducing the private sector to drive higher productivity growth.

Specifically, the government is hoping that increasing the expected return on investment through reductions in investment-related taxes and business costs will spur a transformation in the UK economy not seen since before the 2008 financial crisis. Studies and recent history indicate that other measures may be more effective at inducing the rates of business investment growth that this government needs to achieve.

In this article, we look at: exactly how the government hopes to achieve economic growth, and how effective can it be.

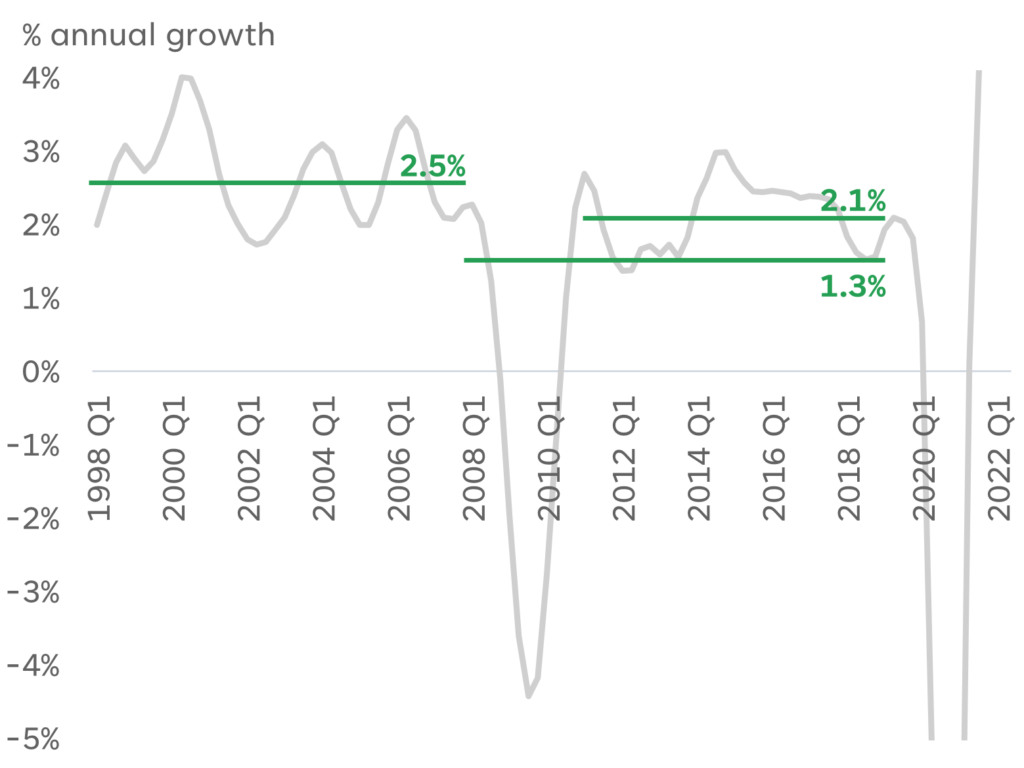

Chart 1: UK output growth and trend rates

Source: ONS.

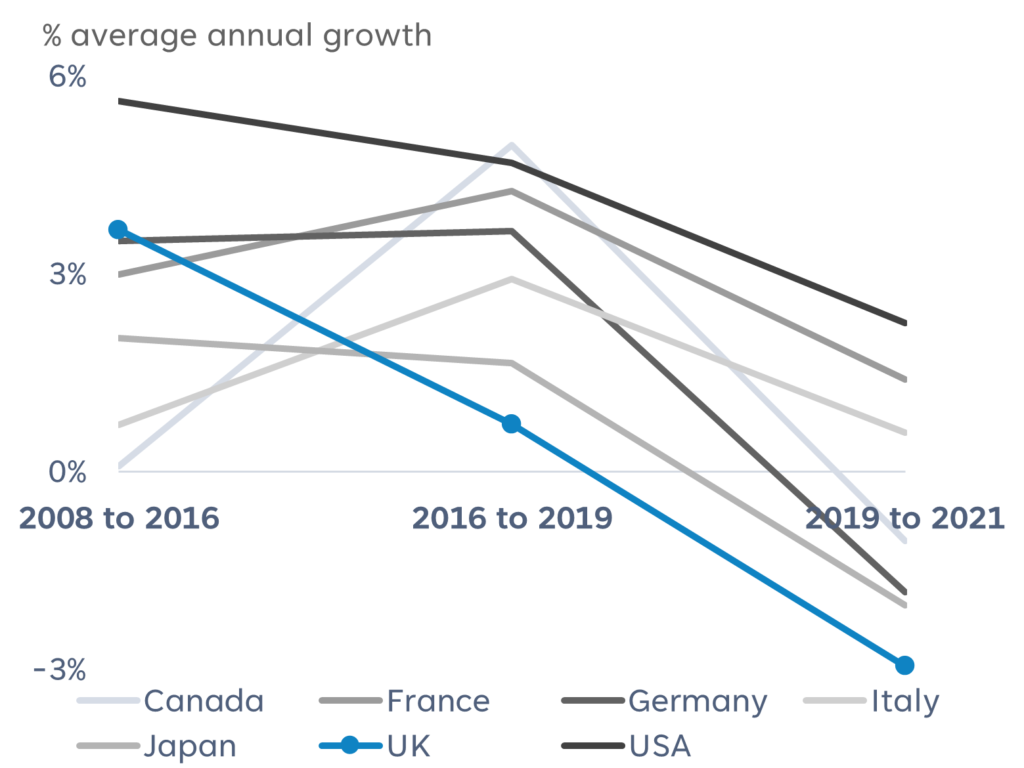

Chart 2: Components of economic growth

Source: ONS.

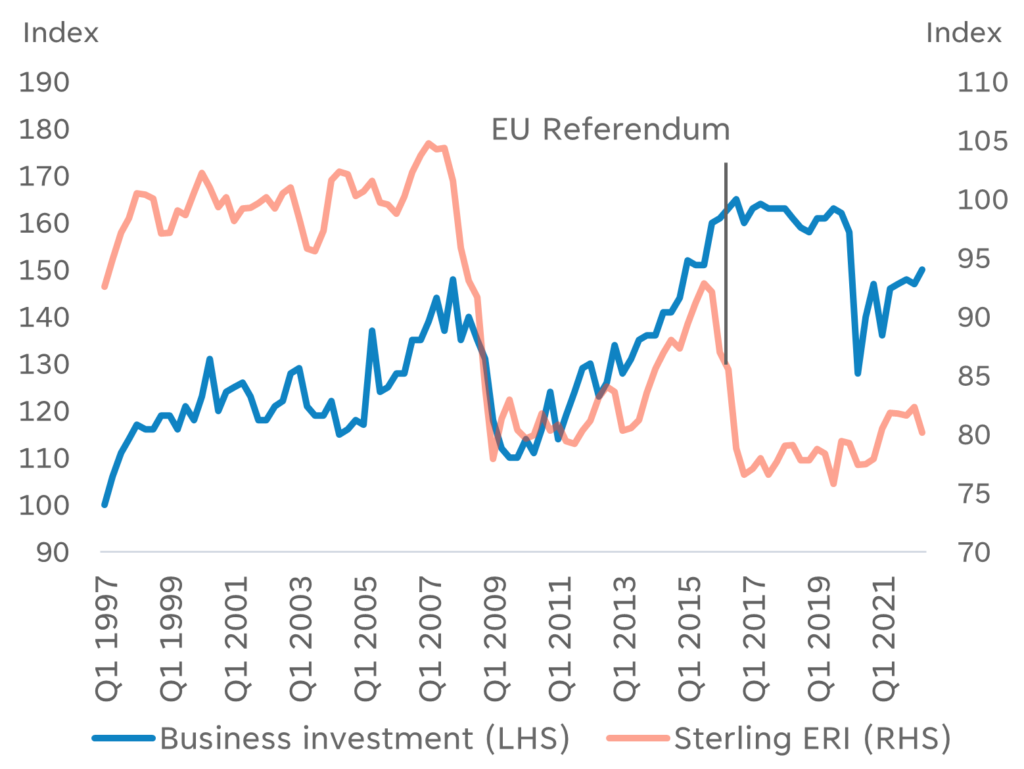

Chart 3: Evolution of UK growth

Source: ONS.

Chart 4: Growth in UK business investment

Source: ONS.

Chart 5: UK business investment and exchange rate index

Source: ONS.

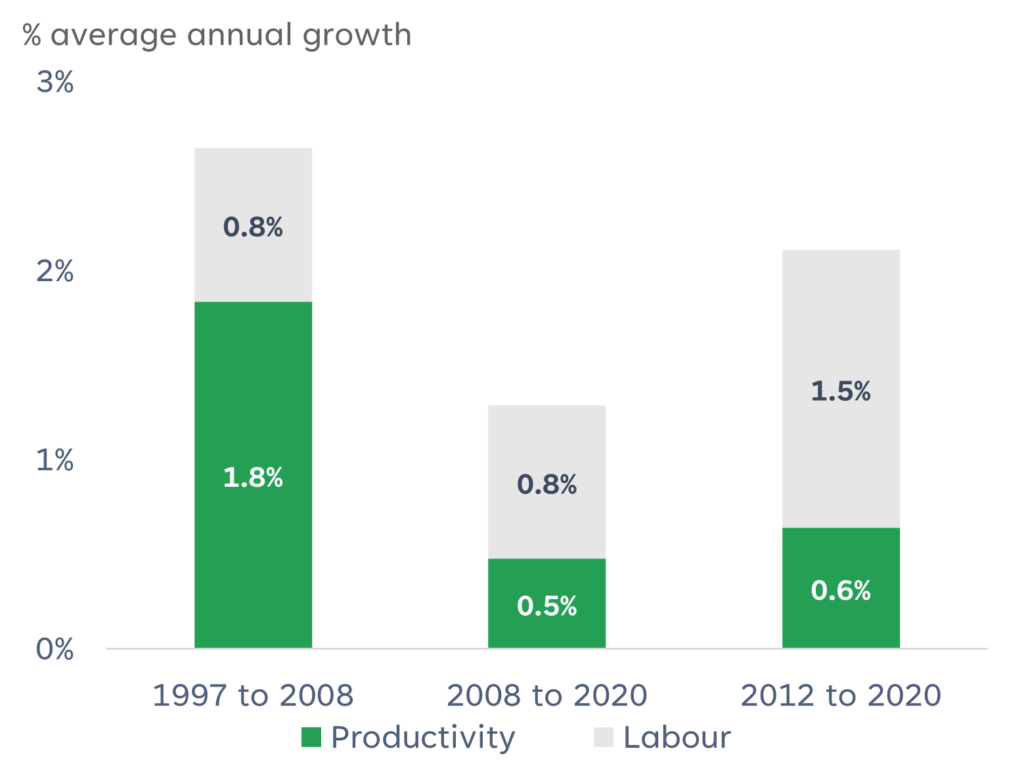

Chart 6: Business investment growth across the G7 countries

Source: OECD.

Introduction

The Truss government’s primary economic policy goal is achieving higher economic growth, specifically to achieve a “trend rate of growth of 2.5%”.[1] The Chancellor’s mini-budget announcement on 23 September 2022 sent shockwaves through financial markets with concerns over significant unfunded tax cuts (expected to be equivalent to 2-4% of GDP per year), lack of details of a fulsome strategy, and appearing to undermine the UK’s traditional economic institutions: the Treasury, OBR, and the Bank of England.

Much attention has focussed on the immediate response to the mini-budget and the subsequent announcements and actions of the UK government and the Bank of England. Not unreasonably so. To date, less attention has been applied to evaluating the merits of this new economic strategy.

A sidenote: even good policy can be fatally undermined by a mishandled communication strategy and initial implementation. Moreover, it is reasonable to ask whether a new long-term economic strategy requiring significant action by the private sector can be successful when it is introduced by an unpopular government with an election that must be held in little over two years. These considerations aside, this article: (i) outlines the calculus of economic growth, (ii) describes the mechanisms the government’s ‘growth plan’ will need to affect, and (iii) evaluates the effectiveness of available policies based on existing evidence.

Calculus of economic growth

The Chancellor’s stated aim is to achieve a “trend rate of growth of 2.5%”. This is a medium to long term goal calculated as a multiple year, average annual GDP growth rate. Typically, such trends are measured over the course of a full business cycle, which can range from 3 to 10 or more years.

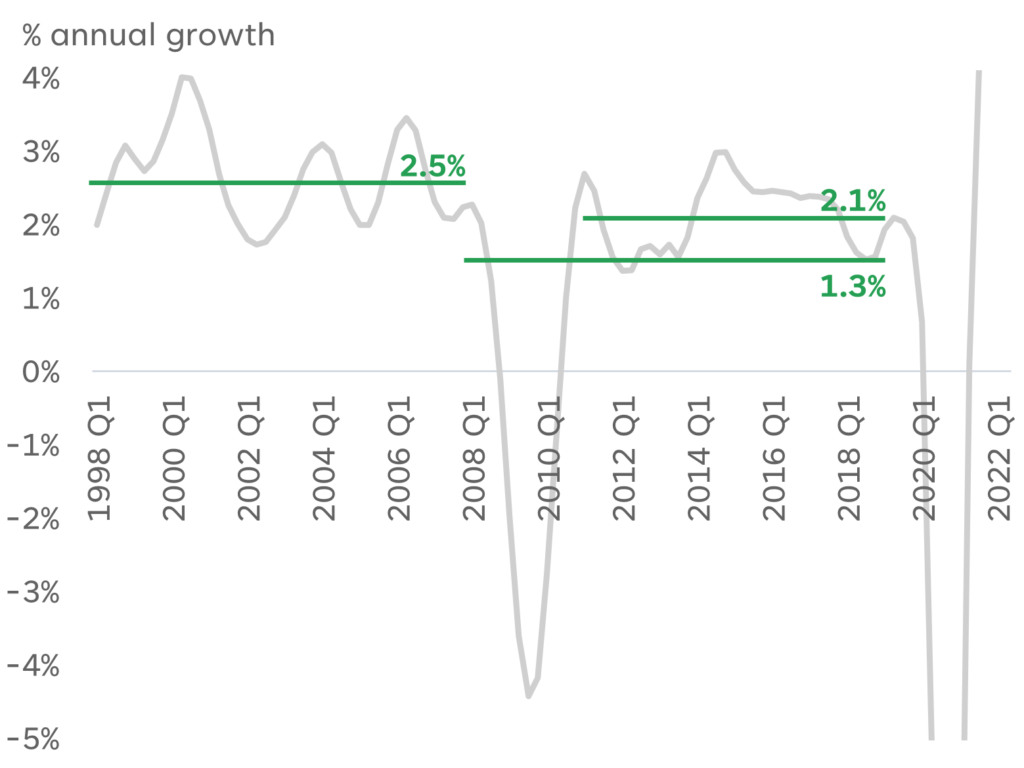

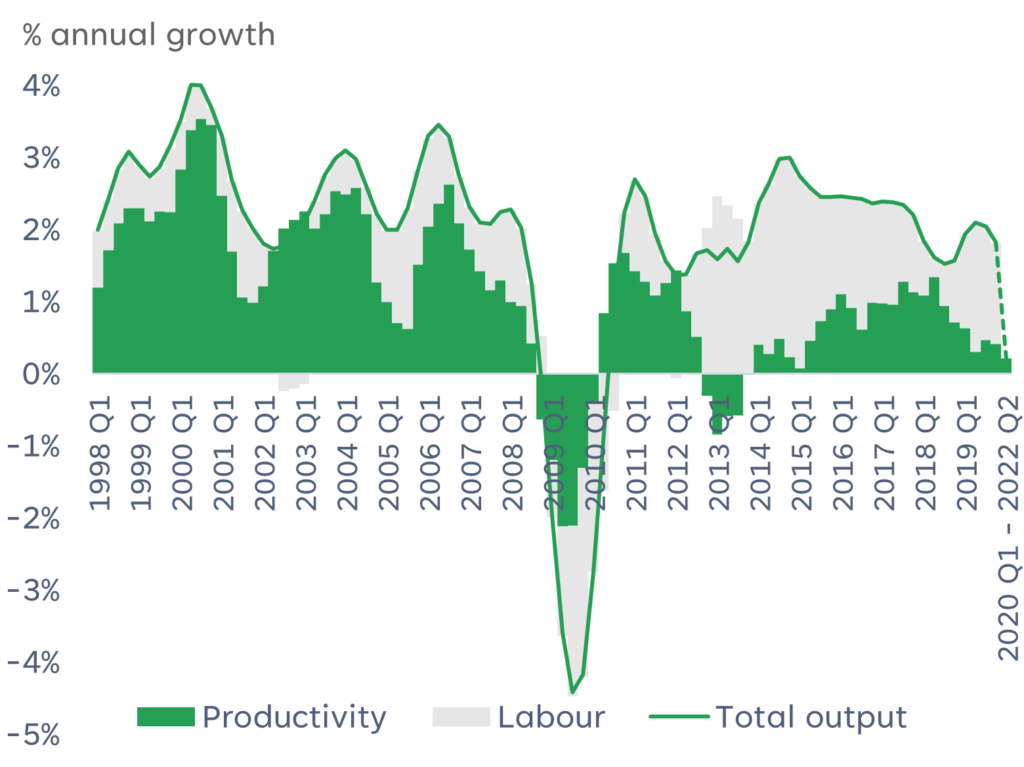

Chart 1 shows UK annual output growth and some measures of trend. Prior to the 2008 financial crisis, the trend annual growth rate was around 2.5%. But this fell to 1.3% in the following period to the end of 2019. Excluding the impact of the financial crisis, the average growth rate in the stable period from 2012 to the end of 2019 was still below the pre-pandemic trend rate at just over 2%. Moreover, the development of the overall trend masks an even starker, and more problematic, development between these periods.

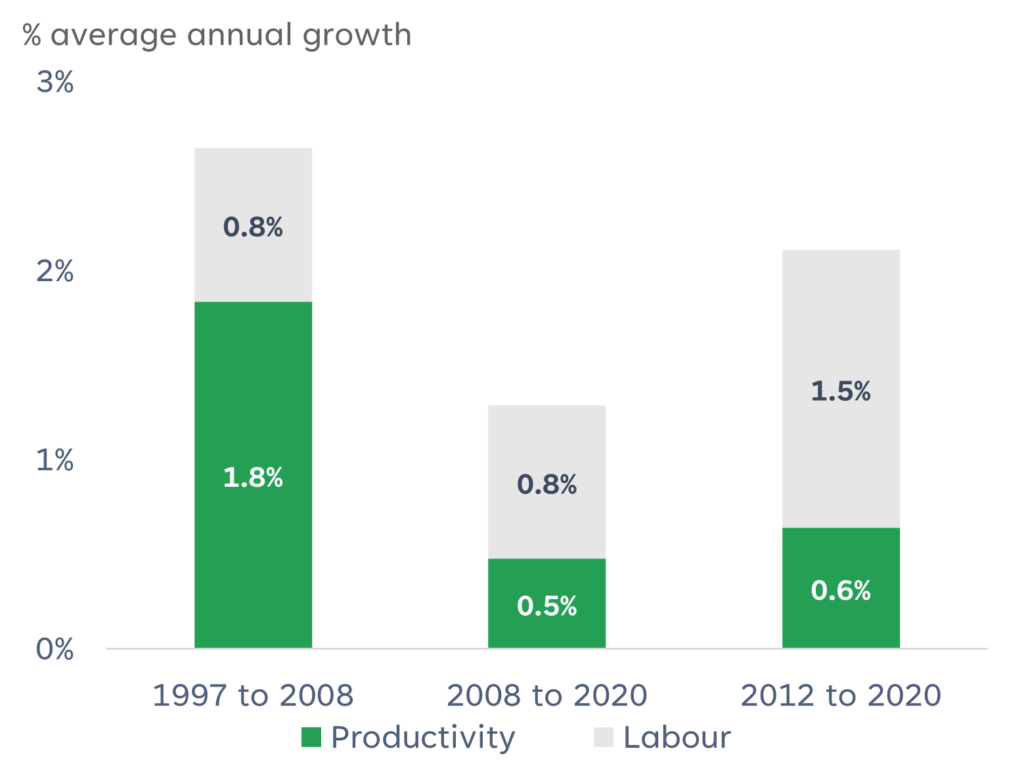

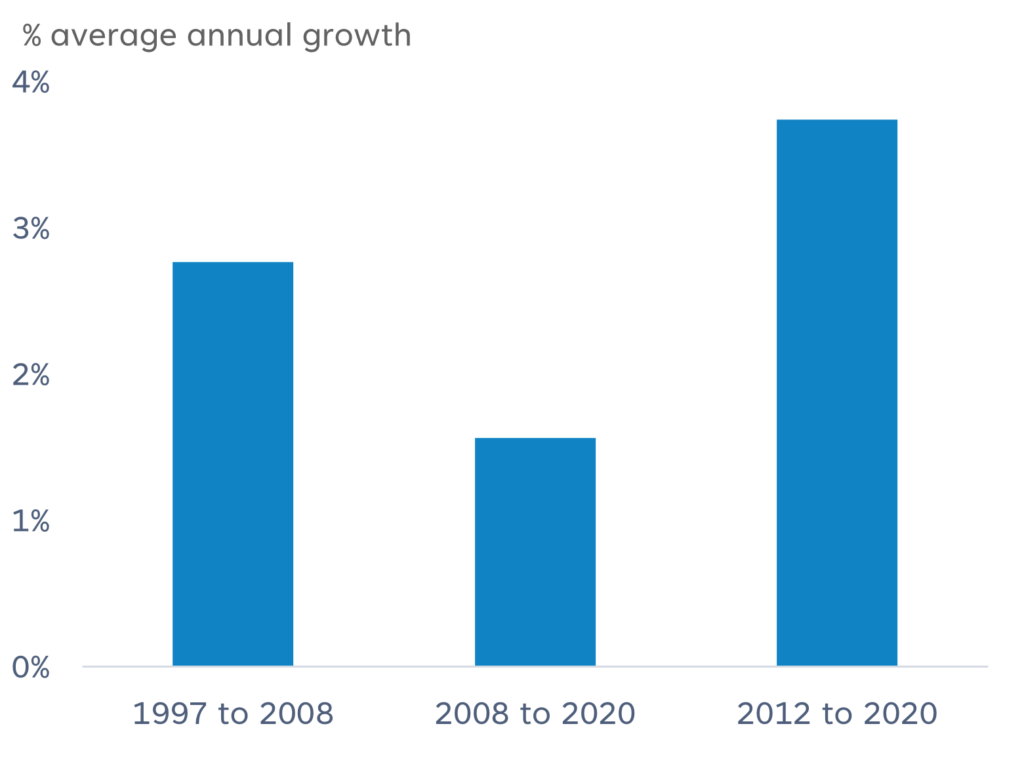

Economic growth can be split into two components: (i) growth in total labour hours worked (“effort”), and (ii) growth in output per hour worked (“productivity”). Between 1997 and 2008, additional effort accounted for 0.8% of average annual growth while productivity accounted for almost 2% (see Chart 2). Between 2008 and 2020, additional effort continued to account for 0.8% of average annual growth while productivity growth fell to just 0.5%. Between 2012 and 2020 the primary driver of growth was additional hours worked and not productivity.

Chart 1: UK output growth and trend rates

Source: ONS.

Chart 2: Components of economic growth

Source: ONS.

Targeting productivity

The government’s growth plan policies will likely include some labour market reforms, such as encouraging the economically inactive into the labour force and encouraging inward migration. However, the unemployment rate and redundancy rate are at 15-year lows and existing job vacancies are at historically high levels, while the economically inactive are overwhelmingly caregivers, retired, students and increasingly the long-term sick; so there is little domestic spare labour capacity.[2] The UK continues to see net inward migration but inward EU migration has slowed or potentially reversed since 2020[3], while post-Brexit visa rules have added frictions for firms looking to employ workers from outside of the UK.[4] Therefore, the UK is most likely to struggle to maintain the recent trend growth in labour hours worked rather than this contributing further to higher trend growth in the medium to long-term.

The UK government will need to unlock significant productivity growth to achieve higher economic growth. The lack of productivity growth since the financial crisis has been coined the “productivity puzzle”. There have been a range of explanations provided, including mismatches in labour market skills and employment requirements, low R&D and infrastructure investment, a broad reduction in competition across the economy, and low demand growth since the 2008 financial crisis.[5]

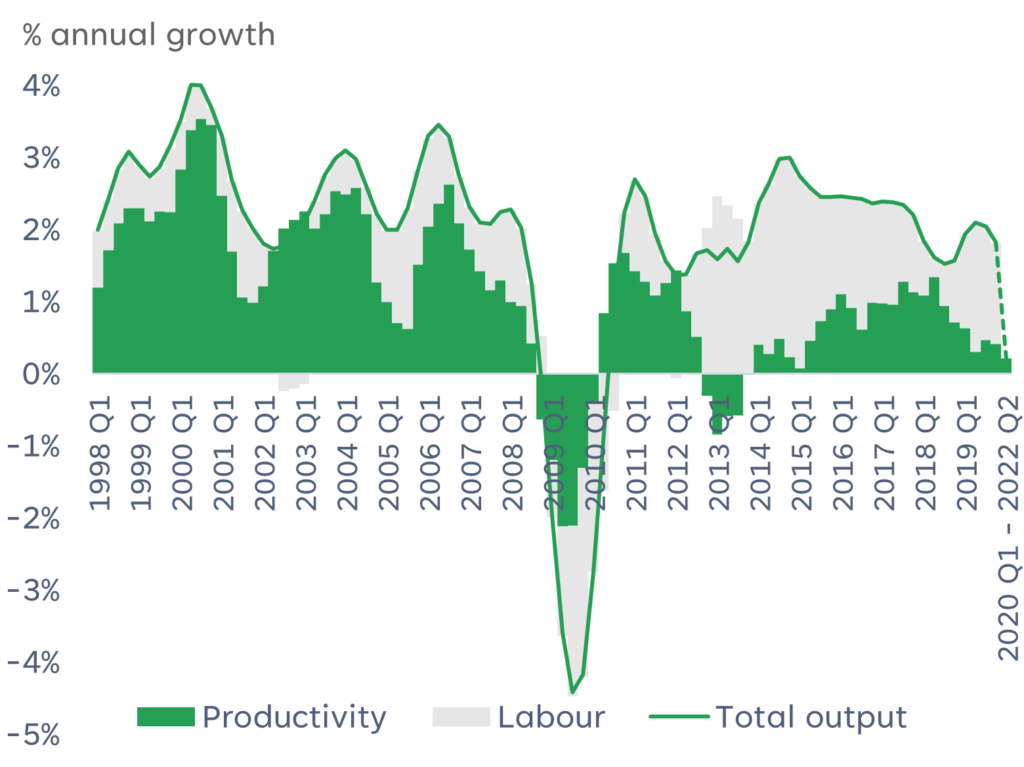

Chart 3: Evolution of UK growth

Source: ONS.

Business investment: the panacea?

The Chancellor’s mini-budget revealed that the government will rely on business investment to drive productivity growth. Importantly, whether it considers that higher growth in business investment alone is sufficient to achieve higher long-term economic growth will be borne out in the policies yet to be announced.

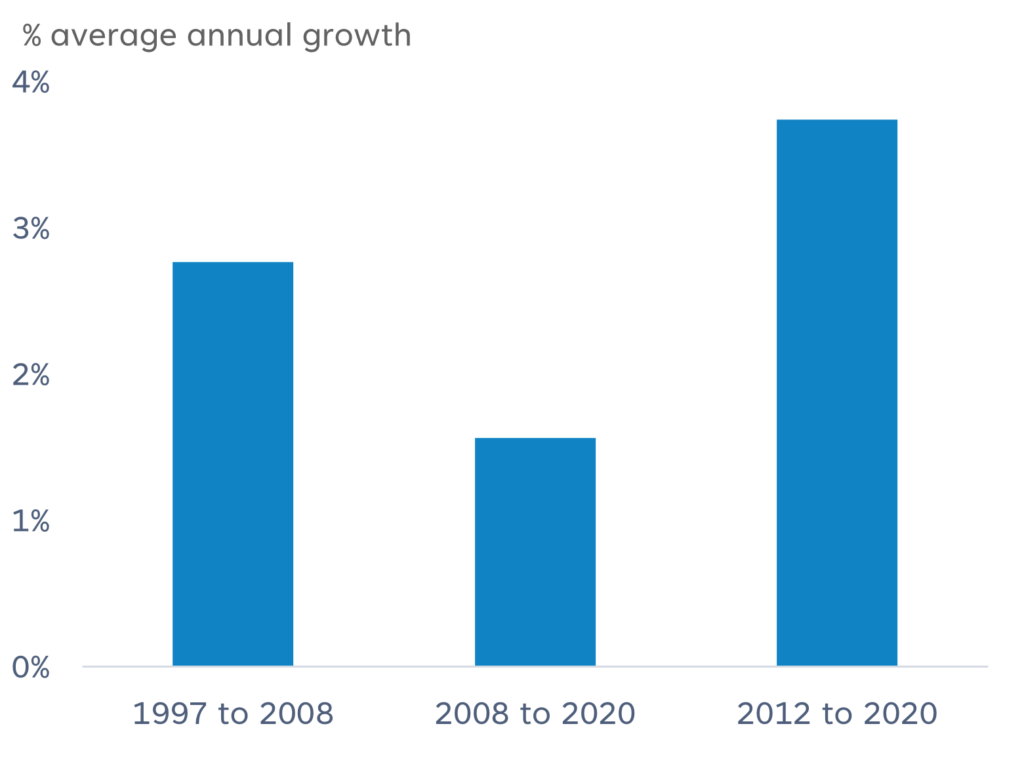

Prior to the 2008 financial crisis, business investment growth was significantly higher than in the following period to 2020 (see Chart 4). However, between 2012 and 2020, business investment grew at an even faster rate in an eight-year period that achieved minimal productivity growth. While expected lag effects caution over-interpreting a simple comparison of productivity and business investment growth over discrete time periods; it appears that business investment alone may not guarantee economic growth.

We believe that strong business investment is a necessary condition for improving productivity growth. Targeted policies to encourage the creation, adoption and dispersion of new technologies and innovative processes at the sector and industry levels are also likely to be important as is greater public investment in infrastructure.[6]

Furthermore, we believe that policy to increase competitive intensity across all sectors of the economy can play a significant role to improve overall productivity growth. The CMA’s own 2020 report on the state of competition in the UK found a broad reduction in competition happened across the UK economy following the 2008 financial crisis, this has been slow to correct, and established incumbents across all major sectors are now increasingly able to maintain their market dominance.[7]

Chart 4: Growth in UK business investment

Source: ONS.

Stimulating policies

The UK government appears to believe that the primary impediment for business investment has been a low expected return on investment which can be remedied by deregulation and investment-related and wealth-related tax cuts. The UK government has:

- reversed a planned increase in corporation tax;

- reduced labour-related taxes and levies, dividend taxes and industry-specific taxes (housing stamp duty and alcohol duty);

- (largely) resisted imposing windfall taxes on energy companies; and

- stated it will announce a series of deregulation reforms intended to reduce business costs related to land and building planning, digital infrastructure, immigration, and the environment.

The government is betting heavily that business investment will be strongly incentivised with policies to increase the expected return on investment. However, if such policies lead to persistently higher long-term interest rate expectations – due to inflationary pressures from government deficit-driven demand – then the financing costs of investment will be greater than it would otherwise have been.

Investment zones

A major policy that the government has partially announced is the creation of ‘investment zones’ across the UK with further tax, infrastructure, and regulatory incentives to promote concentrated geographical areas of business investment and development. Similar industrial zones exist in Europe, North America and across developing countries. These zones can take various forms including:

- free trade zones or export processing zones that are designed to attract foreign investment for trade-related and export-orientated industries; and

- special economic zones typically setup in economically disadvantaged areas to incentivise regional economic development.

The intended benefits of these industrial zones include higher employment and better paying jobs, human capital development (employment training and skills), secondary economic impacts on the local economy, and spillover effects for the broader economy of wider adoption of the technology. However, studies indicate that industrial zones present risks including detrimental labour conditions and treatment, negative environmental impacts, and can partially or fully crowd-out business investment that would have occurred in other areas of a country leading to lower tax receipts with minimal additive impact to economic growth.

Importance of trade

However, there is possibly a far more fundamental obstacle for business investment in the UK. Empirical studies show that cost efficiency is a primary motivation for foreign investment in developing economies but for developed economies the primary motivation is access to markets (with cost efficiency an ancillary motivation at best).[8] That is, investment in developed economies is often seeking to establish access, or consolidate its position, in large markets.

The UK has a population of 67 million with EUR 1.5 trillion of annual household spending (as of 2019). By contrast, the remaining EU single market has a population of 462 million with EUR 7.7 trillion of annual household spending (as of 2019). Access to the European single market was a major factor for much of the foreign investment in the UK over the past two decades, especially the ability to process and easily transport intermediate goods across national borders.

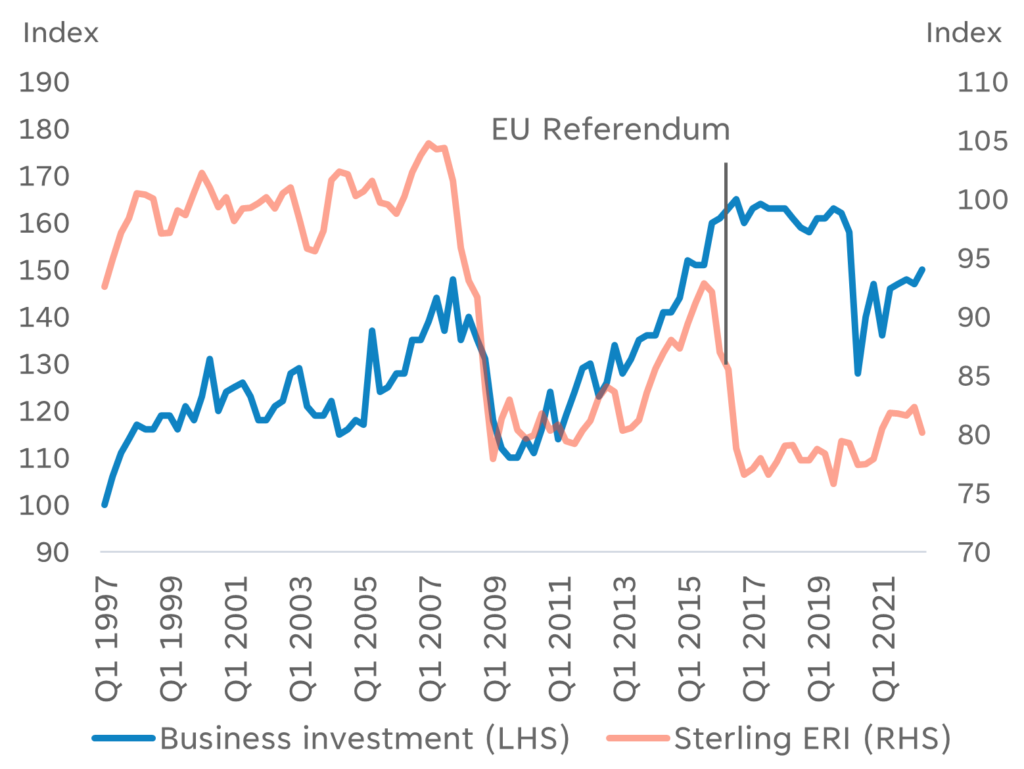

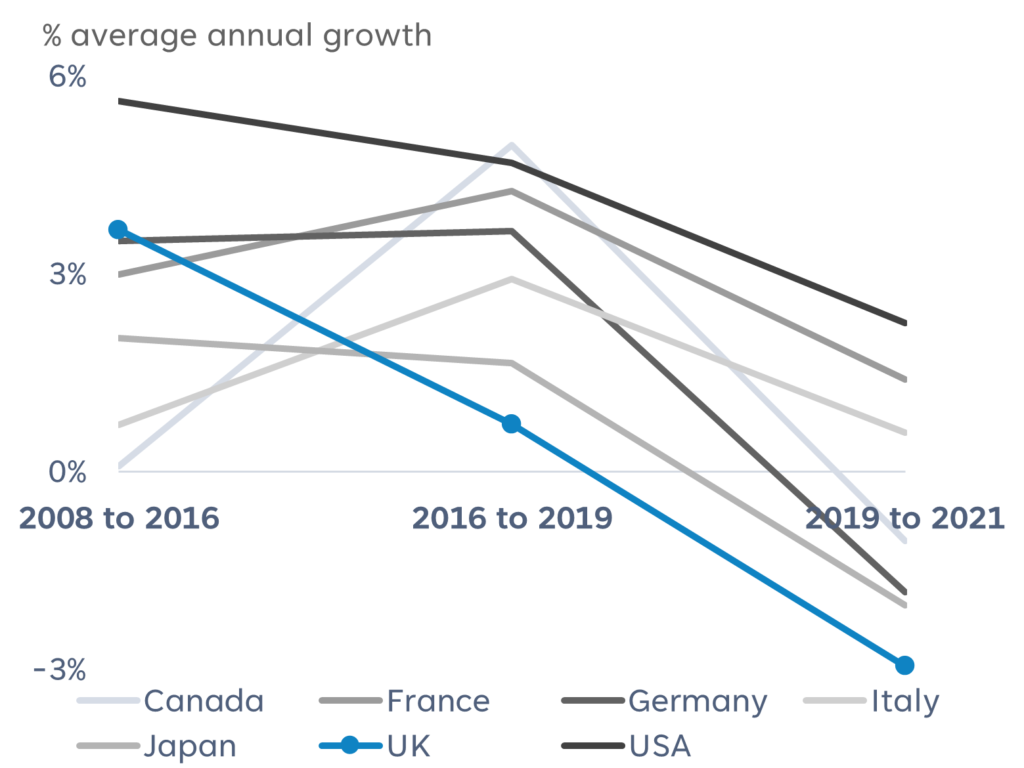

The EU referendum result in 2016 coincided with the sharp arrest of significant growth in UK business investment (see Chart 5); this has been in spite of the pronounced devaluation of Sterling (i.e. making investment in the UK cheaper in foreign currency terms). Furthermore, the UK had achieved the strongest growth in UK business investment across the G7, bar the USA, between 2008 and 2016 (see Chart 6). Yet, between 2016 and 2019, the UK slumped to the weakest growth of all G7 countries by some margin and has also struggled the most to bounce back since the onset of the pandemic.

The Chancellor’s mini-budget speech mentioned “invest” or “investment” 18 times but did not mention “export” or “international trade” once. We are inclined to believe that the UK government is acutely aware of the need to improve trade relations with its major partners (the EU, the USA, and others) for the success of its economic growth strategy but currently has neither the domestic political capital or diplomatic bargaining power to make significant near-term improvements to existing trade partnerships.

Chart 5: UK business investment and exchange rate index

Source: ONS.

Chart 6: Business investment growth across the G7 countries

Source: OECD.

In conclusion

If the Truss government’s new economic strategy is allowed to proceed (a big if, currently), then it will be betting large sums of foregone future tax receipts on policies designed to induce significant growth in business investment by increasing the expected return on investment. Which, in turn, the government is hoping will be the catalyst of greater productivity growth in the medium to long-term.

Each of these links:

- lower taxes & business costs; leads to

- higher business investment growth; leads to

- higher productivity growth

are complex, uncertain, and will almost surely rely on additional policy at the micro-level (i.e. industry and sector policies) and macro-level (i.e. trade and competition policy).

Directionally, it is reasonable to expect that increasing the expected return on investment will induce more business investment. However, the key issue is magnitude – not direction – because cuts to corporation tax, labour-related taxes and dividend taxes affect tax receipts from all economic activity not just the incremental activity induced by these policies. Evidence suggests that market access, not cost efficiency, is the primary driver of investment in developed economies; so structural issues in the economy such as trade openness and economy-wide competitive intensity may be more effective policy to induce greater business investment.

Will greater business investment lead to higher productivity growth? It is reasonable to believe that it is necessary; but smart, detailed, and targeted policy will also likely be required to foment the creation, adoption and dissemination of new technologies and innovative processes throughout the economy.

What is more certain, is that none of this will be proved either way by the turn of the next general election in January 2025 at the latest.

[1] The Growth Plan 2022 speech – GOV.UK (www.gov.uk)

[2] Labour market overview, UK – Office for National Statistics (ons.gov.uk), Employment in the UK – Office for National Statistics (ons.gov.uk)

[3] EU Migration to and from the UK – Migration Observatory – The Migration Observatory (ox.ac.uk)

[4] How is the End of Free Movement Affecting the Low-wage Labour Force in the UK? – Migration Observatory – The Migration Observatory (ox.ac.uk)

[5] Explaining the UK’s productivity slowdown: Views of leading economists | CEPR

[6] Economic growth, public, and private investment returns in 17 OECD economies | SpringerLink

[7] The State of UK Competition Report April 2022 – GOV.UK (www.gov.uk)

[8] Foreign direct investment and its drivers: a global and EU perspective (europa.eu), Determinants of FDI inflows in advanced economies: Does the quality of economic structures matter? (europa.eu) and Empirical Insights on Market Access and Foreign Direct Investment (unctad.org)